Journey through Eduard Bersudsky's Art

by Anna Battista

Steam rises from the bowl of borsch in front of me. The red little flowers

painted on the birch spoon lose their shapes when I raise the wooden piece

of cutlery, loaded with blood red beetroot and broth, to my mouth. The

table I'm sitting at is made of wood. No tablecloth covers it. Outside it's

cold and snowing. The borsch is hot and reassuring. For an instant it feels

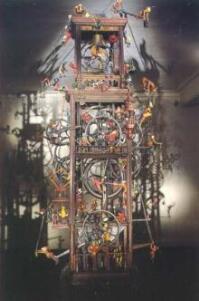

like being in Russia. Then I look around the room: weird shadows are

projected on the walls, they are created by several kinetic sculptures that

populate most of the room. They are arranged along two sides of the room,

leaving free an aisle occupied by beautiful wooden tables, chairs and

armchairs. The sculptures are made of metal scraps, wooden figures, Singer

sewing machines, wheels and other assorted junk.

Steam rises from the bowl of borsch in front of me. The red little flowers

painted on the birch spoon lose their shapes when I raise the wooden piece

of cutlery, loaded with blood red beetroot and broth, to my mouth. The

table I'm sitting at is made of wood. No tablecloth covers it. Outside it's

cold and snowing. The borsch is hot and reassuring. For an instant it feels

like being in Russia. Then I look around the room: weird shadows are

projected on the walls, they are created by several kinetic sculptures that

populate most of the room. They are arranged along two sides of the room,

leaving free an aisle occupied by beautiful wooden tables, chairs and

armchairs. The sculptures are made of metal scraps, wooden figures, Singer

sewing machines, wheels and other assorted junk.

I'm not in Russia, definitely, I'm in Eduard Bersudsky's gallery, Sharmanka, in Glasgow's King Street. The pieces of furniture exhibited among his sculptures are works by the late Tim Stead, a close friend of Eduard. Actually, this place rather than being a gallery is a proper theatre. Just a few minutes ago a small crowd of visitors assisted to the Sunday show: the visitors smiled, laughed or simply frowned trying to understand what the sculptures represented or how they managed to move. Right after the last visitor went away, I reminded Tatiana Jakovskaya, the director of the theatre, how, five years ago, I found myself by absolute chance in the Sharmanka theatre where I was offered her Russian hospitality. On that occasion Tatiana had offered me some tea in a Russian birch cup and had told me the story of how she and artist Eduard Bersudsky, both Russian Jews, emigrated from Russia and arrived in Glasgow in 1993.

"Oh, wait! This time I have something else for you!" Tatiana exclaims in a

thick Russian accent, then disappears in the kitchen and returns with two

steaming bowls of borsch. Tatiana is the artistic partner and wife of

Eduard Bersudsky, better known in Glasgow for his kinetic sculptures

exhibited all over Britain and at the Sharmanka Kinetic Theatre, his gallery.

Eduard and Tatiana recently went to Jerusalem, where the Bloomsfield Science

Museum, part of Jerusalem Hebrew University, held an exhibition of Eduard's

sculptures. "Jerusalem was great!" Tatiana proclaims, recollecting, "We have

families and friends there. In the last ten or twenty years a million of Russian Jews

emigrated from Russia to Israel. So, going there for us was like being at

home in Russia."

"Oh, wait! This time I have something else for you!" Tatiana exclaims in a

thick Russian accent, then disappears in the kitchen and returns with two

steaming bowls of borsch. Tatiana is the artistic partner and wife of

Eduard Bersudsky, better known in Glasgow for his kinetic sculptures

exhibited all over Britain and at the Sharmanka Kinetic Theatre, his gallery.

Eduard and Tatiana recently went to Jerusalem, where the Bloomsfield Science

Museum, part of Jerusalem Hebrew University, held an exhibition of Eduard's

sculptures. "Jerusalem was great!" Tatiana proclaims, recollecting, "We have

families and friends there. In the last ten or twenty years a million of Russian Jews

emigrated from Russia to Israel. So, going there for us was like being at

home in Russia."

"The Russian Jews who emigrated brought to Israel the intelligentsia: they are artists, musicians, doctors, lawyers, engineers and mathematicians," she says. "It was very difficult for these Jews integrating in the local community when they first arrived in Israel, because they had forgotten their old Jewish traditions for three generations. These people arrived in the country without knowing anything about their own roots because in Russia they couldn't practice their religion. At present they seem to be really absorbed in the local society. While in Jerusalem, as first thing we had a private exhibition for one hundred people, they were all our friends and relatives from all over Israel. Watching Eduard's machines they were laughing and crying, because they can understand better than any other audience the meaning of the sculptures, since they can recognise the culture where we came from. The exhibition was planned for three months, but it was later extended for one more month. The sculptures travelled to Jerusalem in sea containers, we went to Jerusalem to install the exhibition and to dismantle it, but we didn't stay there for four months. It was amazing working with the museum crew there because they knew how to make the machines work. There was an Arab boy from East Jerusalem, a genius, who invented this special control system, a sort of remote control, with which you could operate the machines. In the same way you can switch on and off your telly, you could switch on and off the machines. The people in the museum crew there were very gifted. The machines played through two thousand performances, practically no stop and the exhibition was visited by fifty thousand people. Now Bloomsfield Science Museum wants a permanent piece."

The Jerusalem exhibition seems to have united different races and populations. "In Jerusalem you have four languages, at our exhibition we had people from different cultures and they all appreciated it," Tatiana nods, "Our exhibition was pure emotional communication. At a certain point, in the museum where we had the exhibition, there was a group of Jewish children, a group of Arab children, a group of soldiers of the Israeli army and a group of religious Jews. Our electric man was Jewish and the electronic man was Arab. I can assure you that most people want peace in the Middle East."

I wonder if things would have been different for Tatiana and Eduard if they had settled in Jerusalem rather than Glasgow. "At the beginning we wanted to settle in Jerusalem, we were told 'Sorry, we are a small country, we can't cope with one more talented Jew from Russia!' You see, too many gifted Jews went to Israel. I think that if we had moved to Israel we wouldn't have now an exhibition in Jerusalem!" Tatiana jokes, then she explains, "What Eduard is doing is more European, it doesn't suit the South of Europe. Besides, you couldn't find a scrap in Israel because it's a young country and the wood is terribly expensive there. Eduard's art thrives on the beautiful British industrial design. In Russia he was using pieces of old furniture, now he's finally using proper tools."

Eduard is at present also having an exhibition in London at the Theatre Museum, where his automata will be performing until September 2003. But preparing the London exhibition has been apparently more difficult than preparing the Jerusalem one. "At first we connected the machines to a computer and you had to press two buttons to make them move, but they told us it was too complicated for the staff and asked us to reduce it to one button! They don't have a technician in London and they have a part time electrician, so we have to travel there every month to fix the machines. Usually, the machines exhibited there do a limited number of performances because some of them are the eldest fragile pieces Eduard made in Russia and can't stand more than two performances a day. Right now there are two performances a day of wood machines and two performances a day of metal machines, the latter are new machines. Another piece which is performing in London is 'Noah's Ark'. It was performing at the Royal National Theatre in January. Eduard created it for the Mime Festival, but, in the end, there wasn't any Sharmanka exhibition at the Festival and the Royal National Theatre decided to keep it for a year. That was our first appearance in London. We have a very good relationship with the Theatre Museum and they want to do more things with us."

Though, there are plans to remove Eduard's sculpture 'Titanic' from Glasgow's Gallery of Modern Art, since, apparently, there isn't any more space at the GoMA for it, Eduard is now working on something that proves how much he's loved by Glasgow. Indeed, the City of Glasgow will soon have a new work of art, a clock, representing the patron of the town, St. Mungo. Eduard is still working on the wood, bronze and metal life-size statue of St. Mungo that will be installed in the renewed Tron Steeple, facing Trongate and Argyle Street. "The Tron Steeple is still in scaffolding," Tatiana shrugs, "They said it will be ready for the clock at the end of March or beginning of April, but I have a feeling that it will be ready at the end of April, because they are not allowed to work up there on cold days. Right now it completely depends on the weather. The Tron Steeple is a very old building, so it was really decayed and it is taking them a long time to restore it. St. Mungo is still in the workshop," Tatiana reveals to me, adding that we'll visit Eduard in his workshop later on.

"St. Mungo was commissioned by Glasgow Building Preservation Trust. A guy who now works for the Merchant City Townscape Heritage Initiative saw 'The Millennium Clock', came here and said 'I want something for Glasgow. Please, try to find an idea for the Tron Steeple.' At the beginning we had a budget of ten thousand pounds for a small wooden sculpture that would appear from inside the steeple twice a day to chime for a minute. The sculpture would have been installed on the first level of the steeple. Then we discovered that there is actually no window on that level, the window that you see is a fake one and there is no hole in the wall, so there was no space for the statue. We later decided to move one level up and to change the project. St. Mungo would have been a wooden man's size figure. The budget for this project was about thirty thousand pounds since, though Eduard is having a very modest artistic fee, the installation and construction are expensive. Two local businesses, Cafe' Gandolfi and blacksmith A.L.Sillars, supported the project joining Glasgow Building Preservation Trust and Glasgow Lord Provost Millennium Fund. The project also received a grant from Art and Business New Partners."

"We had planned to do an oak figure, but we had eight weeks of rain and the trunk that had been reserved for us by Glasgow parks and donated by Glasgow City Council, had turned into a sponge. We decided to make only the head, hands and feet out of oak, the rest would have been metal. After two weeks the oak head Eduard had carved started cracking and we thought 'OK, what now?' Our metal engineer Andrew said he knew a guy who could cast it in bronze for a reasonable price. But we didn't have the money to do it even if it was for a 'reasonable price'. We asked one of the sponsors of 'The Millennium Clock', Gordon Fraser Charitable Trust, to help us. In three days we got an answer: they said yes! So, I would say that St. Mungo was done thanks to 'The Millennium Clock'. We recently had a reception for St. Mungo because we wanted to show people what's going on and we also wanted to see their reaction. We invited fifty people and in the end a hundred came as everybody had brought a friend! All the people who were at the reception loved the statue. I was amazed by their reaction because it's their patron saint. We were worried, we said 'we are foreigners, what do we know about it?' I hope that St. Mungo loves how we depicted him, so maybe he will help us to survive in Glasgow!" Tatiana concludes, smiling.

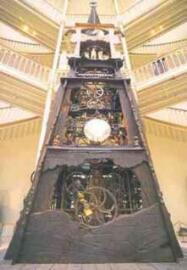

Since Tatiana mentioned it, I can't do without asking

her to tell me the story of 'The Millennium Clock'. The Millennium Clock

Tower is now permanently installed in Edinburgh Royal Museum, marking the

hours of the visitors. The clock combines the coloured glass panels of

Swedish Annica Sandström, the clock-making artistry of German Jürgen

Tübbecke, the art of carving wood of British designer Tim Stead and the

automata of Eduard Bersudsky. "'The Millennium Clock' was originally

planned for Glasgow," Tatiana remembers, "It was Julian Spalding's idea for

Kelvingrove Art Gallery. Then Julian stopped working there and we couldn't

go on with our project. Later on we had and exhibition at the Royal Museum

in Edinburgh for the Millennium Festival and they asked us if we had a

project for the millennium. We said yes, but we didn't have the money for

it. They asked us to reapply to the Millennium Festival Fund, we did it and

won a huge competition. A while back Edinburgh wanted to get rid of 'The

Millennium Clock' and we asked Glasgow to take it but they didn't want it.

In the end the clock got permanent residency at the Royal Museum. At

present 'The Millennium Clock' has played five minute performances every

hour for three years."

Since Tatiana mentioned it, I can't do without asking

her to tell me the story of 'The Millennium Clock'. The Millennium Clock

Tower is now permanently installed in Edinburgh Royal Museum, marking the

hours of the visitors. The clock combines the coloured glass panels of

Swedish Annica Sandström, the clock-making artistry of German Jürgen

Tübbecke, the art of carving wood of British designer Tim Stead and the

automata of Eduard Bersudsky. "'The Millennium Clock' was originally

planned for Glasgow," Tatiana remembers, "It was Julian Spalding's idea for

Kelvingrove Art Gallery. Then Julian stopped working there and we couldn't

go on with our project. Later on we had and exhibition at the Royal Museum

in Edinburgh for the Millennium Festival and they asked us if we had a

project for the millennium. We said yes, but we didn't have the money for

it. They asked us to reapply to the Millennium Festival Fund, we did it and

won a huge competition. A while back Edinburgh wanted to get rid of 'The

Millennium Clock' and we asked Glasgow to take it but they didn't want it.

In the end the clock got permanent residency at the Royal Museum. At

present 'The Millennium Clock' has played five minute performances every

hour for three years."

While eating my borsch I look around and admire the sculptures: they are

giants made of intricate metal structures: "Proletarian Greetings to the

Master Jean Tinguely", a homage to kinetic sculptures artist Tinguely,

includes a cage, a wheelchair and a skull; "Time of Rats" represents

Russia, a metal mole controlled by wooden rats enjoying themselves on its

back; "The Last Eagle of the Highlands" is a mechanical sculpture made of

metal and skulls dedicated to a scientist who spent years studying the

behaviour of the Scottish eagles. I wonder how long it takes to build

these works of art. "'Tower of Pisa' took half a year, but it depends from

the sculpture," Tatiana explains, "'Tower of Babylon' took three years. We

left Russia in 1993, ten years ago. In these ten years Eduard made twice

more machines than he had done in Russia in the previous 15 years. That's

because he can now do it full time and he's got proper tools and

components. The machines he made in Russia are very fragile because the

motor is fifty years old. The oldest sculpture we have at the Sharmanka

Kinetic Theatre is a small one that we don't use in the performances, it's

called Sharmanka which means 'Barrel Organ'. For an exhibition at the

Theatre Museum we had to renew each sculpture because they were far from

European standards and weren't safe. We invest quite a lot of money in each

sculpture: we have an electrician from Israel and a mechanic from Russia.

Sometimes, for some of the machines you can't change only the motor, you

have to build them from scratch. It's a little bit difficult to exhibit in

the USA, because of electrical standards and different frequencies, but

it's something we can talk about."

While eating my borsch I look around and admire the sculptures: they are

giants made of intricate metal structures: "Proletarian Greetings to the

Master Jean Tinguely", a homage to kinetic sculptures artist Tinguely,

includes a cage, a wheelchair and a skull; "Time of Rats" represents

Russia, a metal mole controlled by wooden rats enjoying themselves on its

back; "The Last Eagle of the Highlands" is a mechanical sculpture made of

metal and skulls dedicated to a scientist who spent years studying the

behaviour of the Scottish eagles. I wonder how long it takes to build

these works of art. "'Tower of Pisa' took half a year, but it depends from

the sculpture," Tatiana explains, "'Tower of Babylon' took three years. We

left Russia in 1993, ten years ago. In these ten years Eduard made twice

more machines than he had done in Russia in the previous 15 years. That's

because he can now do it full time and he's got proper tools and

components. The machines he made in Russia are very fragile because the

motor is fifty years old. The oldest sculpture we have at the Sharmanka

Kinetic Theatre is a small one that we don't use in the performances, it's

called Sharmanka which means 'Barrel Organ'. For an exhibition at the

Theatre Museum we had to renew each sculpture because they were far from

European standards and weren't safe. We invest quite a lot of money in each

sculpture: we have an electrician from Israel and a mechanic from Russia.

Sometimes, for some of the machines you can't change only the motor, you

have to build them from scratch. It's a little bit difficult to exhibit in

the USA, because of electrical standards and different frequencies, but

it's something we can talk about."

Music is another important component of Eduard's machines. "The music is especially designed for the sculptures," Tatiana underlines, "'The Last Eagle of the Highlands' was done in 1994, it was inspired by Mike McGrady. We went to the Highlands and met this American scientist who worked there at the time and told us a story about golden eagles living in Scotland. The music that accompanies it is very moving and was recorded by Julian Spalding's wife. I can't stand professional singers and professional soundtracks, so I asked this nice woman, who's an amateur, to record it. When you hear it you realise that she feels what she sings. She did the song for the sculpture so she knew what she was doing. The soundtrack for 'Pisa Tower' instead was played by Lev Atlas. Also 'Noah's Ark' is accompanied by Russian music played by Lev Atlas. The latter is Eduard's fave music and it used to be Tim Stead's favourite music, Lev played it also at Tim's funeral. Lev Atlas is the owner of the Russian Café Cossachok in Glasgow King Street. Lev was thinking about opening a Russian restaurant when we opened the gallery. The place downstairs was available and he decided that it would have been nice to open the restaurant near to us so that it would have been a connection. Ours is a good professional collaboration rather than a personal friendship. We recently celebrated Lev's birthday here in the gallery!"

Music does not only accompany Eduard's sculptures: there are composers who were actually inspired by Eduard's works, one of them is Brian Irvine who recorded a CD entitled Bersudsky's Machines: "Bersudsky's Machines is a piece of music we at present don't use here," Tatiana points out, "We learnt about it in 1998 when a guy called from Belfast saying 'I'm Brian Irvine, a composer, I wrote music inspired by Eduard's machines, could you please bring one or two of them to Belfast?' We brought with us 'Time for Rats' and two other small machines. We loved his music. Now Brian is a very well known jazz musician. His music is not for wide audiences, since he plays very experimental jazz, but he's doing very well. He played at Glasgow Jazz Festival two years ago and we met him. Brian also went to visit the Gallery of Modern Art in Glasgow, since he didn't know that we had a piece there. Originally, he had made only one piece of music, but after he saw the video we sent him, he made a whole album inspired by Eduard's machines. At some point Eduard wanted him to make an application to Creative Scotland. The idea was to create a kinetic sculpture that would play Brian's music. It was a music machine that children would have been able to play with, but the idea wasn't selected."

Tatiana and Eduard are busy now with the gallery going under reconstruction: "The gallery was flooded a while back. Luckily, the ceiling collapsed while most of the machines were in Jerusalem or London, otherwise it would have destroyed a couple of them. It was a very scary situation. It rained and rained for the whole summer and for three months they couldn't stop the water since they didn't know where the water was coming from. The fabric of the building gave way and the rain got into the building through the stone. You see, this building is 150 years old. Glasgow City Council has recently decided to turn the building into an artistic place. On all the five floors there will be galleries, film studios or independent studios for young artists. It sounds great! The idea is very reasonable because there are so many galleries here, but the building is in a very bad condition. If everything will go according to this plan, it will take two years. We'll all have to evacuate the building for one or two years and then we'll be back in a fully reconstructed building and all the galleries will be linked, by corridors and lifts. The Sharmanka will be back on the first floor and not on the second floor."

"Plans are beautiful, but I don't know how long we will be able to keep going. When the machines will be back from London, we won't have the space in the theatre for at least two machines. The Jerusalem exhibition was planned two years ago, but the London exhibition came as a surprise. While we were packing for Jerusalem, we were called to do the London exhibition. Eduard built for Jerusalem two new sculptures, one is 'Rag and Bone Man', which had a first night in Jerusalem, and he built two new machines for London. We also have to get back the sculptures from the Gallery of Modern Art."

But apart from being busy with their gallery Tatiana and Eduard are busy at present with another project: "We won a third National Lottery Grant: the first was to built Sharmanka, the second for 'The Millennium Clock', the third for a three year educational programme. We are having fifty school performance workshops: some of the schools come from England, from London, others from the Orkney Islands. It's a big programme that also helps us to survive."

During our chat, Tatiana explained a lot about their trip from Russia to Scotland, about Eduard's sculptures and about their exhibition, but what is art for her? "Unfortunately, there is a tremendous amount of money involved in the question 'What is art?' The art market is controlled by a few people in New York and London. If you're not in the mainstream you're not there. Eduard's works are often exhibited in science and technology museums rather than in art galleries. We sometimes sold some sculptures to private collectors: Eduard made twelve kinetic birds one different from the other and people seem to like them a lot. One raven is at Billy Connolly's house, one fled to Italy, four or five are in London, one recently went to Spain. A lot of people use it to meet and greet visitors. Eduard does art for public places. When he does something small he would rather keep it for himself and we would like to find more public places where Eduard's sculptures might be exhibited. For example, we would love to have sculptures in a shopping mall. 'Rag and Bone' man is the sort of sculpture that could go everywhere. I hope we can find a place also for 'Noah's Ark', which is too big for this place, being four and a half metres long. That's the sort of sculpture that would be suitable for a public space. 'Noah's Ark' is a fantastic piece which I love very much and I think it could go everywhere, it can work in daylight and it might be exhibited in shopping malls so that children would have something to look at, it would be a meeting point for children. Until now we didn't have positive answers to this suggestion. Let's bring art to shopping malls! Just give people some joy!" Tatiana exclaims, then she waits for me to finish the borsch, stands up and leads me to Eduard's workshop.

A smell of wood and

metal hangs in the room. The shelves of the workshops are stacked with

tools, scraps of metal, wood, nuts and bolts. The window is opened, outside

it's dark, snow is falling. For a while, it feels like being in Russia

again. The statue of St. Mungo occupies most of the room. Master Eduard is

working on a wooden sculpture, a small bird. Electric cables run inside the

wooden body of the bird, they will give life to the little sculpture.

Eduard stops for a while to greet me, Tatiana acting as translator. Then

Tatiana turns the clock on and St. Mungo's starts moving. The statue is not

yet completed, the body is still a metal skeleton, but the model gives an

idea of what the clock will look like: the fish leaps at St. Mungo's feet,

the bird perched on his crosier flaps its wings, the bell rings and St.

Mungo beatifically nods his head. I feel privileged at being admitted in

this sancta sanctorum. While the statue is still moving, Tatiana shows me

the bronze casts of the head, feet and hands. Then Eduard breaks his

silence and starts talking while resuming his work. He asks me if I like

Italian director Federico Fellini's movies. I nod and tell him about my

favourite scene taken from a Fellini movie: the ring-a-ring-a-roses of the

mad characters on the beach at the end of 8 ½. Eduard nods in

acknowledgment, while Tatiana reminds me that one of Eduard's kinetic works

is called "La Strada", in homage to Fellini. Eduard then stops working

again, goes towards his TV set, rummages among a pile of video tapes,

selects one and shows it to me. It's a video of Pier Paolo Pasolini's Il

Decamerone in Russian, Pasolini is another of his favourite directors. I

nod and smile at him. We come from different countries, but we seem to have

something in common.

A smell of wood and

metal hangs in the room. The shelves of the workshops are stacked with

tools, scraps of metal, wood, nuts and bolts. The window is opened, outside

it's dark, snow is falling. For a while, it feels like being in Russia

again. The statue of St. Mungo occupies most of the room. Master Eduard is

working on a wooden sculpture, a small bird. Electric cables run inside the

wooden body of the bird, they will give life to the little sculpture.

Eduard stops for a while to greet me, Tatiana acting as translator. Then

Tatiana turns the clock on and St. Mungo's starts moving. The statue is not

yet completed, the body is still a metal skeleton, but the model gives an

idea of what the clock will look like: the fish leaps at St. Mungo's feet,

the bird perched on his crosier flaps its wings, the bell rings and St.

Mungo beatifically nods his head. I feel privileged at being admitted in

this sancta sanctorum. While the statue is still moving, Tatiana shows me

the bronze casts of the head, feet and hands. Then Eduard breaks his

silence and starts talking while resuming his work. He asks me if I like

Italian director Federico Fellini's movies. I nod and tell him about my

favourite scene taken from a Fellini movie: the ring-a-ring-a-roses of the

mad characters on the beach at the end of 8 ½. Eduard nods in

acknowledgment, while Tatiana reminds me that one of Eduard's kinetic works

is called "La Strada", in homage to Fellini. Eduard then stops working

again, goes towards his TV set, rummages among a pile of video tapes,

selects one and shows it to me. It's a video of Pier Paolo Pasolini's Il

Decamerone in Russian, Pasolini is another of his favourite directors. I

nod and smile at him. We come from different countries, but we seem to have

something in common.

Before going away I give a last look at the sculptures collected in the Sharmanka Kinetic Theatre. "Jock's Joke", "Crusader", "Pisa Tower", "Aurora", "Forget Me Not", "Nickodym" are all sleeping quietly. The Sharmanka door closes behind me and I think about Tatiana talking about Mikhail Bulgakov in connection with Eduard's sculptures. In Bulgakov's novel The Master and Margarita, the heroine asks at the request of Woland, master of black magic and devil, how thousands of guests and musicians can fit into an ordinary Moscow flat. She's answered "because of the fifth dimension". When I'm in Argyle Street, I turn towards Eduard's window: the light is still on, Master Eduard is in his own fourth dimension, cramped and crowded not with people, but with clocks, bolts and bells clinking and tinkling away. The snow is still falling. It's silently falling on Argyle Street, on the living, on the dead and on Eduard Bersudsky's dreams.

Special thanks to Tatiana and Eduard for the hospitality!

For further info please visit the Sharmanka site at www.sharmanka.co.uk. All pictures above are from the web site.

Copyright (c) 2005 erasing clouds |

|