Facts and Fictions: Interview with writer Suhayl Saadi

by anna battista

Relocation. Immigration. Visa Allocation. The words, printed on a solicitor firm's ad on the back of a bus, sway in front of me. Relocation. Immigration. Visa Allocation. I repeat them in my head like a mantra. I'm sitting on another bus, closely following the one with the ad on and, from my position, I can read the words, printed in black on a white background, through the front window. It's an ordinary day in Glasgow, Scotland. The bus with the ad is heading towards the city centre and it's passing through Victoria Road: to its left there's the area called Pollokshields and to its further left Shields Road. In the former there is a higher population of Asian people, in particular in the area around Albert Drive where Islamic bookshops, food shops, halaal butchers and shops selling colourful saris can also be seen. It's emblematic that the bus with that particular ad on is passing around here: it's as if it were constantly referring to the procedure many of the people living around these parts had to go through in their life.

There's a recently published novel that uses Glasgow's Pollokshields as the background for some of the events narrated in the story and tries to explore the tensions and the contrasts in the mind of a young man of Asian origins whose parents emigrated from Lahore to Glasgow in the '50s. The book also analyses the confusion that perennially reigns in your mind when you live in another country and don't feel you belong to your country of origin anymore, yet there's still something buried within you that connects you to it. The book is called Psychoraag (Black & White Publishing) and its author is Suhayl Saadi. Born in Yorkshire, England, in 1961, Saadi moved with his family to Scotland in 1964. His parents came to Britain from Lahore, Pakistan in 1955. "My mother's family were Persian-speaking Afghani," Saadi recounts while we're sitting in a Glasgow café, rain pitter-pattering against the windows, "her family had moved from Afghanistan to what was then British India in the 19th century as a result of what used to be called the Great Game, a kind of power game between imperial Russia and imperial Britain for the control of Afghanistan. They were aristocrats and had a lot of money at that time, they kept their own language and their own citizenship when they moved and they only married within that family group. My mother's generation was the first to marry outside it. My father was originally from Agra which is a city in Northern India and at the time of the partition of India in 1947 he was a medical student in Lahore. The partition happened during the summer holidays, in August, so he was stranded in India and had to get back to his college. He did, despite what was happening around him. This was indeed a time of massive population movements and massacres, two million of people were killed. My father travelled by train and arrived in Lahore to complete his studies. Here he met my mother who had volunteered to work in a refugee camp. They then emigrated to Great Britain because my father wanted to get postgraduate qualifications, though the intention was to go back. Then my brother and I arrived, we started going to school, our parents got enmeshed in the society and things in Pakistan didn't work out the way they had anticipated they would do economically or politically, so we ended up in staying in Britain."

There's a recently published novel that uses Glasgow's Pollokshields as the background for some of the events narrated in the story and tries to explore the tensions and the contrasts in the mind of a young man of Asian origins whose parents emigrated from Lahore to Glasgow in the '50s. The book also analyses the confusion that perennially reigns in your mind when you live in another country and don't feel you belong to your country of origin anymore, yet there's still something buried within you that connects you to it. The book is called Psychoraag (Black & White Publishing) and its author is Suhayl Saadi. Born in Yorkshire, England, in 1961, Saadi moved with his family to Scotland in 1964. His parents came to Britain from Lahore, Pakistan in 1955. "My mother's family were Persian-speaking Afghani," Saadi recounts while we're sitting in a Glasgow café, rain pitter-pattering against the windows, "her family had moved from Afghanistan to what was then British India in the 19th century as a result of what used to be called the Great Game, a kind of power game between imperial Russia and imperial Britain for the control of Afghanistan. They were aristocrats and had a lot of money at that time, they kept their own language and their own citizenship when they moved and they only married within that family group. My mother's generation was the first to marry outside it. My father was originally from Agra which is a city in Northern India and at the time of the partition of India in 1947 he was a medical student in Lahore. The partition happened during the summer holidays, in August, so he was stranded in India and had to get back to his college. He did, despite what was happening around him. This was indeed a time of massive population movements and massacres, two million of people were killed. My father travelled by train and arrived in Lahore to complete his studies. Here he met my mother who had volunteered to work in a refugee camp. They then emigrated to Great Britain because my father wanted to get postgraduate qualifications, though the intention was to go back. Then my brother and I arrived, we started going to school, our parents got enmeshed in the society and things in Pakistan didn't work out the way they had anticipated they would do economically or politically, so we ended up in staying in Britain."

Psychoraag is the story of Scottish Asian DJ Zaf, who is broadcasting for the very last time his night programme The Junnune Show on Radio Chaandni, an Asian radio station based in a deconsecrated church in Glasgow. Zaf thinks the last night of his programme will be a quiet one, but his expectations are frustrated by a series of events. Suhayl started writing the novel in the spring of 1999, hoping to publish it in 2002, then his previous publisher Polygon was sold and the book had to wait for quite a while before being released by Black & White Publishing. Suhayl wrote part of the book, and exactly 34-35,000 words of it in New York last year. "The novel already had a fast pace, because of the nature of the subject matter, but New York was an ideal place to complete it," he states, "I was in Chelsea, Manhattan, on a Scottish Arts Council official development fund, a grant you can get to advance your career as an artist. I also had been invited to do readings because a fragment of the novel had come out on an anthology of Scottish writing by a local publisher, so I managed to finance the trip. Besides, before going, I contacted an organisation called The Teachers and Writers Collaborative, which helps teachers and writers to get together and do things in schools, and I got to do through them some workshops in Manhattan schools which was great. Chelsea was the right place where to finish the novel because it's a very creative place and it's very cosmopolitan. A critic in Edinburgh referred to the novel not as a 'Scottish' or a 'British' novel - whatever those terms mean - but as a 'New York City novel', because of the pace and style and the eclectic subject matter."

Suhayl's novel could be defined also as a psychogeographical novel: though particular areas of Glasgow are well described, they are a sort of excuse to explore Zaf's mind. Like the barge in Alexander Trocchi's Young Adam or the motorcycle in Andre Pieyre de Mandiargues' La Motocyclette are excuses to travel through time and memory, so is the radio station in Psychoraag. "The radio station is a vehicle," Suhayl explains, "it's not a portrayal of any real radio station." The book is mostly written in Glaswegian interspersed with Urdu and with various song lyrics, while the story of Zaf's parents eloping from Lahore is written in Standard English, almost to reflect the time when they left and their own idea of what the English language sounded like. "I've heard people talking in a Scottish accent for almost all of my life and I've read authors such as James Kelman and others who use the demotic, so I suppose all those writers must have been and influence in some way," Suhayl says, "but I don't draw especially from a particular author. I always draw from authors outside Scotland. Italo Calvino, Jorge Louis Borges, the nouveau roman French school, weird Spanish writers that burnt themselves to death, Albanian and Turkish writers, these are the stuff I really like. I use different styles in my writing because I want my works to be symphonic, as if the different voices of the characters were different instruments."

Psychoraag is a symphonic novel not only because of the different styles the author uses, but also because of the music Zaf is playing. Music defines Zaf, whose identity lays "not in a flag or in a particular concretisation of a transcendent Supreme Being but in a chord, a bar, a vocal reaching beyond itself." Zaf is constantly programming the decks, putting on more tracks, from Bollywood hits to Primal Scream, from Jimmy Page and Robert Plant to Asian Dub Foundation. He is also constantly scribbling down the titles of the various songs on a piece of paper, which towards the end of the book becomes a sort of metaphor for his life. "His playlist was almost black with the various stains of the night. Wine, blood, spunk, vomit, skin, bone, flesh, brain. Zaf had emptied his body on to the clean white surface of the paper," Suhayl writes. The book also includes a discography and Zaf's complete playlist. "I wanted to add the playlist in the book since I started writing it, but it kept expanding," Suhayl says, "My original idea was to release the book with a CD in the back cover, with some of the songs played by Zaf, but it is very difficult for a small publisher to get permission to do it. One day I'd like to do it though, I think that would be ideal, not only as a selling point, but also as a fun thing. I don't like too much some of the tracks I included in the book, because they're not my favourite tracks, but Zaf's. The ones I like personally are the psychedelic rock ones such as The Beatles' 'Rain', I love that song, but I also love The Byrds and any kind of music that tries to go beyond the limits of your mind. I like music that scratches the surface and goes backwards in time and tries to seek out hidden connections, for example music by Radio Tarifa or Les Negresses Vertes, because they explore different forms of music and try to melt them together. I think their kind of polyglot vision of reality is actually a more accurate imitation of reality than any kind of monolithic, totemic vision of any kind of cultural stream. I'm not so much into hip hop, but I think French hip hop is far superior compared to a lot of the macho hip hop crap that comes from the States. French seems to be a good language for hip hop, in the same way as Arabic is a good language for that because it has got a mixture of harshness and mellifluousness. I quite often use music to write, but not the music I mention in the book, because a lot of that is vocal and it's too distracting, I mostly use instrumental music. I have a CD player right next to my computer and I put it on very quietly just above audible level and listen to dissonant music. I don't use rock music because it's too rhythmic, I use modern dissonant classical music or very late Liszt, or dissonant jazz such as Coltrane or Ayler. I also use music as a synesthetic tool to get rid of all the distractions, switch my mind onto something and condition myself to work."

Psychoraag is a symphonic novel not only because of the different styles the author uses, but also because of the music Zaf is playing. Music defines Zaf, whose identity lays "not in a flag or in a particular concretisation of a transcendent Supreme Being but in a chord, a bar, a vocal reaching beyond itself." Zaf is constantly programming the decks, putting on more tracks, from Bollywood hits to Primal Scream, from Jimmy Page and Robert Plant to Asian Dub Foundation. He is also constantly scribbling down the titles of the various songs on a piece of paper, which towards the end of the book becomes a sort of metaphor for his life. "His playlist was almost black with the various stains of the night. Wine, blood, spunk, vomit, skin, bone, flesh, brain. Zaf had emptied his body on to the clean white surface of the paper," Suhayl writes. The book also includes a discography and Zaf's complete playlist. "I wanted to add the playlist in the book since I started writing it, but it kept expanding," Suhayl says, "My original idea was to release the book with a CD in the back cover, with some of the songs played by Zaf, but it is very difficult for a small publisher to get permission to do it. One day I'd like to do it though, I think that would be ideal, not only as a selling point, but also as a fun thing. I don't like too much some of the tracks I included in the book, because they're not my favourite tracks, but Zaf's. The ones I like personally are the psychedelic rock ones such as The Beatles' 'Rain', I love that song, but I also love The Byrds and any kind of music that tries to go beyond the limits of your mind. I like music that scratches the surface and goes backwards in time and tries to seek out hidden connections, for example music by Radio Tarifa or Les Negresses Vertes, because they explore different forms of music and try to melt them together. I think their kind of polyglot vision of reality is actually a more accurate imitation of reality than any kind of monolithic, totemic vision of any kind of cultural stream. I'm not so much into hip hop, but I think French hip hop is far superior compared to a lot of the macho hip hop crap that comes from the States. French seems to be a good language for hip hop, in the same way as Arabic is a good language for that because it has got a mixture of harshness and mellifluousness. I quite often use music to write, but not the music I mention in the book, because a lot of that is vocal and it's too distracting, I mostly use instrumental music. I have a CD player right next to my computer and I put it on very quietly just above audible level and listen to dissonant music. I don't use rock music because it's too rhythmic, I use modern dissonant classical music or very late Liszt, or dissonant jazz such as Coltrane or Ayler. I also use music as a synesthetic tool to get rid of all the distractions, switch my mind onto something and condition myself to work."

Music also played an important part in Suhayl's life because he got to writing through it, or rather, through music and medicine. "I was good at English and History when I was in school, they were my favourite subjects together with Chemistry, which I found quite imaginative," Suhayl remembers, "at that time I was also told by an English teacher that I could study English at university, but I wanted to study something that was the most difficult thing to get into to prove that I wasn't stupid. I chose medicine, but I didn't do it because I wanted to help people, I did it for purely selfish reasons. During my studies I abrogated my creativity completely and became a sort of Dominican. The only books I read around that time were horror books or something like that and I didn't listen to music. In retrospect, I think I did it because I knew that those things were so powerful that if I let them invade my space they would take over. I then gradually discovered that I didn't actually enjoy medicine much, even though I was and I'm good at it since I still work as a part-time GP. But I realised it wasn't fulfilling, so I began to listen to music towards the end of my medical training, psychedelic music in particular. I was catching up since I was 15 years too late!" he exclaims, "Listening to music relocated my sense of reality and, contemporarily, I began to read real books. I always had this ambition, I wanted to play instruments, I loved music, but I was technically rubbish. But I always wanted to write as well, so I went along to a further education class in the evening. One thing lead to another and I joined a writing group and learnt my craft in a difficult way, which is the only way to do it: going to classes, writing and having your stuff criticised by other people. So, over the years I got better and I got some encouragement. I think the idea of writing was dormant in me. Initially, I started writing as an outlet, as a cathartic thing, but also as a means of going back and taking my revenge upon all the insults I had faced trying to grow up here, it was my way of taking revenge."

From music we go back to talking about Glasgow and about the Asian community living here. At a certain point of the novel, when Zaf is wandering around the Pollokshields area, Suhayl writes "...he crept into the stone ovens of Albert Drive and Leven Street. If Prince Albert only knew! Halaal butchers. Subcontinental grocers, the ubiquitous video shops crammed with noisy amusement machines, the religious bookshops with their glowerin, bearded Holy Willies whose skins had never been touched by yellow dirt and who seemed to live not on food, music or spirit but on fear of jahannam. Silent churches with no visible congregations. Masjids secreted in tenements flats devoid even of Glasgow light. Bearded sisters, ferociously pristine white converts or born-again phoodulanahs, the former of whom dreamed, presumably, of a paradise filled with the stereotypically sleek bodies of tall black men and the latter of a kind of garden party jannat stuffed with slick-headed, roarin twenties gentle men who were so white they were fucking monochrome. The only animals hereabouts were the hippocrites." I ask Suhayl how he thinks the Asian community here will receive his novel. "A while back I read stories on Asian Community Radio at night from 12.00 to 1.00am - that's how I got the germ of the idea for Psychoraag. While reading, I often wondered if anyone was listening, I actually thought nobody was, but I discovered they were, because some people phoned and complained about the language, although I had converted the swear words in my stories into non-swear words. I thought it was good that somebody complained because that meant that somebody was listening. Then, months later I was at a wedding, and this young guy bounces up to me and says 'you are that guy who read stuff on the radio'. He said he remembered a story I read about a gang and said it was a great story. He also asked me if I had been in a gang, I replied I had never been in one and he told me he was 'on the edge of one', which probably meant he was actually involved with a gang and added that my tale exactly described how it feels like to be in a gang. I thought it was a great praise. What I'm doing in my writing and in this book in particular, is confronting pre-existing notions of things. I'm not analysing society from a Salman Rushdie point of view, I'm not an Oxford educated upper class English looking down on people. I'm analytically looking at things through Zaf's eyes, with his gaze, which is a male sight and is also a selfish sight. Zaf is criticising not only his community, but also the host community. With this book I'm kind of trying to confront things which people don't talk about because it's not politically correct to do so. I read fragments of the book in Pakistan to people who could speak English and they loved it. People should not be afraid of scrutinising communities and languages, particularly patriarchal and artificial constructs."

"In Pakistan, things have moved on, here they haven't to some extent. Most of the people who migrated to Glasgow and Bradford, to provincial Britain and not to London or Birmingham, came from very poor rural backgrounds, they were illiterate and came from one or two areas, Mirpur, South of Kashmere, or Fasalabad, in Punjab, and their migration was a chain migration, whole families moved from there. As a consequence of that, they didn't have to re-orientate their minds, they could exist in some ways in a hermetically sealed vacuum at some level internally, whereas in London that's impossible. Here you can live in hermetically sealed communities, the communities are small enough to be able to do that, everybody knows everybody else and they are all from one village. Then when they first came to Great Britain, some of them migrated from England to Scotland and obviously they faced all the usual difficulties, racism and all that and that throws you in on yourself, because you're afraid and you're vulnerable if you're not educated. In these circumstances, the leaders of the community, who are basically men, the patriarchs, become even more powerful, because women don't challenge that state, they're not in the position to do it, and if they do it they can be ostracised. Apart from that, nowadays you also have the injection of this very post-modern phenomenon of Islamic so-called fundamentalism. This injection combined with this kind of inward looking attitude to some extent has enabled some of those communities or elements within those communities to maintain sway over people. That said, in my opinion, mostly multi-cultural Britain works very well, even within Glasgow, though here people live in tenements that are almost like closed perimeters to some extent and don't cross particular lines. In a way, this is self protection and self preservation, but it can lead to problems and oppression, in particular oppression of girls." Though Psychoraag is written, as we said, from a male perspective, there are in the novel a few female characters. One of them is Zaf's Asian ex-girlfriend Zilla, another his new girlfriend Babs, epitome of the concept of whiteness, a third is Ruby who co-hosts a Bollywood programme in the same radio where Zaf works. "All women potentially were seven-veiled Salmah and real women were not granted even the slim chance of salvation which these half-prophets had been accorded," Suhayl writes in the book. He nods when I remind him of this passage, "Guys can get away for a lot more," he states, "In some of my short stories in my collection The Burning Mirror I took female protagonists and I put them in situations in which they might come in some kind of dramatic conflicts and in fact one of the characters in one of the stories, Ruby in 'The Queens of Govan', is also in Psychoraag, because she was such a strong character that she demanded that I wrote more about her."

Suhayl uses quite often in his works a particular expedient, dislocation: often the further you are dislocated from a context, the better you understand it and the better you can write about it. "I was recently writing a novella for a publisher based in Inverness," Suhayl recounts, "and I set it on the south coast of England, because I thought what better than setting something at the other end of the country in the winter and out of season and perhaps having a main character who's not from here but from another country such as Poland? In this way, you instantly create dramatic dislocation, which is a great recipe for dramatic conflict." Dislocation is also at the base of Suhayl's first play, The Dark Island, a love story between a Pakistani doctor and an Outer Hebrides Gaelic singer living in a cave. The play, set in an Outer Hebrides island, had a strong political message, even though it superficially resembled a sort of fable. "I often inject political things into magical stories or vice versa," Suhayl explains, "I love stuff like Juan Rulfo's Pedro Paramo, in the same way I love the epic form and fairytale forms, but I like to use them in a kind of urban realist setting or contemporary setting. For example, The Dark Island was also about the doctor's betrayal of his work in a Pakistani village and the betrayal of his wife, a teacher killed in the village as a result of his betrayal. It's a kind of Lorca type of story and it's very political, since it's about the Pakistani right wing police gangs of the landowners who don't want people to become educated and have health care, so they murder a teacher. In Pakistan these landowners still rule and it still happens there that they sometimes pay the teacher to stay home."

Apart from The Dark Island, Suhayl wrote another play, Saame Sita, Lapland Tales, a Christmas play, which was commissioned to him by a theatre workshop in Edinburgh. The workshop previously commissioned plays based in different parts of the world, last year's play was based in Lapland. "It was a great honour to write the play," Suhayl says, "I had to do some research, then I also contacted the University of Tromso, in Norway, the most northern university in the world and got in touch with local writers and academics. I was very keen not to seem like some guy coming along and appropriating some exotic cultures. In the end I think I managed to write something that was appealing to a general audience who didn't know anything about that culture, but was also true to the culture and not debunking it or making fun of it."

Psychoraag is Suhayl's official debut novel and his bibliography includes poems, a collection of short stories entitled The Burning Mirror (Polygon 2001), plays, essays and articles, but a few years ago he actually wrote another novel, an erotic fiction book. Entitled The Snake and published under the name Melanie Desmoulins, a pseudonym taken from Camille Desmoulins, the Jacobean poet who was beheaded ("Melanie" comes from "melanin", Suhayl underlines, which means "black", so the name was a pun meaning "Black Desmoulins"), the novel was released by cult publisher Creation Books. "The story, which is based in Portugal, is a sort of demonic tale," Suhayl tells me, "it was inspired by Guillaume Apollinaire, Louis Aragon, Anais Nin, the Marquis de Sade and such likes. In The Snake, I took certain concepts from The Story of the Eye and from The Perfume Garden: my protagonist was indeed woman, though she doesn't become a victim in the story as in many erotic novels, but she actually acquires power. At the time, I wouldn't promote the book because I was embarrassed since I was working as a full time GP. You can imagine the headlines which would have appeared on the papers."

Psychoraag is Suhayl's official debut novel and his bibliography includes poems, a collection of short stories entitled The Burning Mirror (Polygon 2001), plays, essays and articles, but a few years ago he actually wrote another novel, an erotic fiction book. Entitled The Snake and published under the name Melanie Desmoulins, a pseudonym taken from Camille Desmoulins, the Jacobean poet who was beheaded ("Melanie" comes from "melanin", Suhayl underlines, which means "black", so the name was a pun meaning "Black Desmoulins"), the novel was released by cult publisher Creation Books. "The story, which is based in Portugal, is a sort of demonic tale," Suhayl tells me, "it was inspired by Guillaume Apollinaire, Louis Aragon, Anais Nin, the Marquis de Sade and such likes. In The Snake, I took certain concepts from The Story of the Eye and from The Perfume Garden: my protagonist was indeed woman, though she doesn't become a victim in the story as in many erotic novels, but she actually acquires power. At the time, I wouldn't promote the book because I was embarrassed since I was working as a full time GP. You can imagine the headlines which would have appeared on the papers."

It is often the case that erotic books are dismissed as second rate books, generally wank books and basically hidden away in bookshops and libraries since too embarrassing or offensive, but, as Suhayl notes, many famous authors wrote an erotic novel at some point in their lives, yet no Scottish author ever did, apart from Alexander Trocchi, who wrote a few while living in France. "Susan Sontag wrote a beautiful foreword in 1967 to the English edition of George Bataille's The Story of the Eye, and she explains in it how erotic themes have always been shut down and misinterpreted here in the Anglophone world, " Suhayl states, "I think erotic literature is a valid genre which goes back to the Song of Solomon and the Bible and it is also a parodic genre. Writing that book broke a lot of literary boundaries for me in many ways, because I'm now able to import sex scenes in my mainstream fiction, I use them because they are part of the physicality."

Erotic fiction leads us to talk about how often particular books are ostracised in Great Britain by the media and by a part of the population: Suhayl was recently involved in The Big Read, a BBC programme which tried to find out which was Great Britain's best-loved novel. "I took part in a programme which also featured Janice Galloway and Louise Welsh," Suhayl remembers "I didn't know exactly what it was about, but we had been asked to bring along books that we liked. I had nothing prepared, apart from a big sack full of books, because I thought it was going to be an informal chat. Then Janice Galloway did a wonderful speech and I thought 'how do I follow that?' I just jotted a couple of things she was talking about then talked about the books I had with me and what they meant to me. Most people hadn't heard about those authors and at the end of the programme some of them asked me further information about them. Then somebody asked me what I thought about the top twenty of the books chosen by people. It featured novels that had been adapted for the big screen such as Lord of the Rings and Rebecca. James Joyce, D.H.Lawrence, Gabriel Garcia Marquez, Vargas Llosa and Victor Hugo weren't there. Another thing that didn't feature there were novellas. I love short stories, but in this country most of the people don't. A novella is an ideal form to read on a bus for example, but many people don't like them because they can't see how a novella can be deep enough to get into it. But well written novellas explore one character and one idea very well and very deeply in only 30,000 words. Besides, novellas are short enough for modern attention span and modern time factors. I think there is a market for novellas in Great Britain, but I also think many people are stuck in the Jane Austen mentality here. There are still people here who think the novel was invented in the 18th century by a few English men, which is not true. Before that there was Cervantes and before that tales of Sinbad, Persian stories and Homer. The dominant dialectic here is the Jane Austen dialectic essentially and that's never been challenged. Joyce challenged it, Beckett challenged it, but they had to go abroad to do it."

Another "problem" with Great Britain is that often white British writers can do whatever they like and write about whatever country they want and still be successful or be taken seriously. A thing which you aren't often allowed to do, if you are from another country and want to write in Britain, about Britain and in English. "Years ago I told an academic that I was fed up writing about Asians, I wanted to write a book about English people," Suhayl says, "he told me 'They won't allow you to do that' and he was right because I never managed to publish such a book."

At present, Suhayl is busy doing readings (he will appear in August at the Edinburgh's Book Festival), lectures like the one he did at Glasgow University during Write To The Point, an annual conference on creative writing, working on another play and collaborating with the students from Edinburgh's Queen Margaret Drama College. He seems to have quite a few plans for the future, though his most important project is a new novel. "The new book will be longer than Psychoraag, but at present I'm only a third of the way through," he reveals, "The story will feature a middle-aged female protagonist and will be set in different parts of the world. The complexity in the next novel will not be through the use of different demotics and different accents, in fact the novel will be in Standard English, but it will be in the narrative. Psychoraag is basically a simple narrative with one main character, while the new novel will have multiple characters and multiple narratives feeding in and it will be based in multiple locations. It will be a different approach and it will have a slower pace than Psychoraag," Suhayl concludes.

While Suhayl is rushing away and I'm saying goodbye, I try to imagine what his next novel will be like: perhaps it will have the same lulling rhythm of songs played by Sufi minstrels, the same energy and anger of Indian rebel poet Kagi Nazrul Islam, the stream of consciousness of James Joyce and the visionary realism slightly tinted with historical and political themes of many Argentinean authors. After all, these elements can already be detected in Psychoraag and in other works by Saadi and are the reasons why his poems, prose, essays and articles are fresh, entertaining and will definitely help him to be included among the new exciting voices of contemporary literature. No, not of English, Scottish or British literature, but of international literature.

Copyright (c) 2005 erasing clouds |

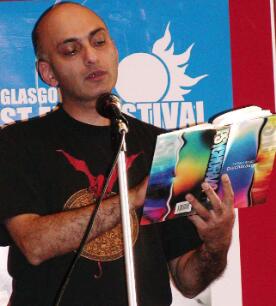

Pic of Suhayl Saadi reading during the West End Festival, Hillhead Library, Glasgow, Scotland, 24th June 2004 by Anna Battista. |