Waltzing the outlaw: Interview with Peter Carey

by Anna Battista

"Once a jolly swagman camped by a Billabong/Under the shade of a Coolabah tree/And he sang as he watched and waited till his billy boiled/'Who'll come a-waltzing Matilda with me?'/Down come a jumbuck to drink at the water hole/Up jumped a swagman and grabbed him in glee/And he sang as he stowed him away in his tucker bag/'You'll come a-waltzing Matilda with me'/Up rode the Squatter a riding his thoroughbred/Up rode the Trooper - one, two, three/'Where's that jumbuck you've got in your tucker bag?'/'You'll come a-waltzing Matilda with me'/But the swagman he up and jumped in the water hole/Drowning himself by the Coolabah tree/And his ghost may be heard as it sings in the Billabong/'Who'll come a-waltzing Matilda with me?'" --"Waltzing Matilda"

At a certain point of the final furious battle between the police and the

members of the so-called Kelly gang, a strange creature arrives on the

scene. It's a sort of monster, with no head, a thick neck and a broad chest

on which bullets seem to bounce back. The true identity of the creature

will be revealed only when, after being shot in his legs, he will fall and

the iron armour he's clad in will be removed, revealing under its solid

protection Ned Kelly, the Australian (Iron)outlaw and national hero, head

of the gang whose story is recalled by Peter Carey in his 2001 Booker Prize-winning novel True History of the Kelly Gang (Faber and Faber).

At a certain point of the final furious battle between the police and the

members of the so-called Kelly gang, a strange creature arrives on the

scene. It's a sort of monster, with no head, a thick neck and a broad chest

on which bullets seem to bounce back. The true identity of the creature

will be revealed only when, after being shot in his legs, he will fall and

the iron armour he's clad in will be removed, revealing under its solid

protection Ned Kelly, the Australian (Iron)outlaw and national hero, head

of the gang whose story is recalled by Peter Carey in his 2001 Booker Prize-winning novel True History of the Kelly Gang (Faber and Faber).

The book recently allowed Carey to also win the Italian Flaiano Award for literature for the year 2002."My friend Patrick McGrath, who's really one of my closest friends, won the Flaiano Award last year and he's at present selling lots and lots of books," Peter Carey explains regarding the second award. "He actually sells very well in Italy, so he keeps on teasing me saying 'I'm big in Italy!' This prize is important to me, not only because Patrick won it before, but because it gives me an opportunity to make new Italian readers," he smiles, revealing, "I don't sell millions of books in this country, so it would be definitely nice to sell more."

Carey, who is considered as one of the most important and famous contemporary Australian authors, started his career as a writer in 1974 with The Fat Man in History. "My family had a General Motors dealership in a small town, they sold cars," Carey recollects about how he ended up writing. "I could have easily had that life, but there wasn't room for me in the business. So that's the only reason why I probably didn't start selling cars to farmers."

From then on collections of stories and novels

followed. One of them, the historical novel Oscar and Lucinda, rewarded

him with the Booker Prize in 1988. But among his works, the book that

probably celebrates Australia best is True History of the Kelly Gang.

"I was born in Australia and lived there until a few years ago," he starts

recounting, "Australia still seems to remain the main subject and obsession

of my novels. I lived in New York City for the past eleven years. I did

once tried to wrote a novel abut the United States, but it was with great

relief that I abandoned it. The reason I abandoned it was that it somehow

occurred to me that there was this great Australian story about an outlaw

called Ned Kelly that had never been told. And what was very interesting to

me from the perspective of the United States was not that he was just an

outlaw like Jesse James, but that this outlaw's story was the single most

important story in our culture. It wasn't like he was Jesse James. It was

more as if he was Thomas Jefferson and Abraham Lincoln and George

Washington rolled into one. In the perspective of New York this looked very

strange, you know, living away from home one has this benefit of seeing

what was familiar as strange to understand. For example, the lyrics of the

song 'Waltzing Matilda', a famous song in Australia that politicians never

seem to be able to accept as our national song, are about a homeless man

who steals a sheep and commits suicide rather than go to jail. This is a

song about heart, in Australia this seems normal, but from the distance of

New York one can see how wonderful and peculiar this is. We love Ned Kelly

in the same way that we sympathise and in a way identify with the homeless

man who committed suicide. I thought Ned Kelly's story was a great story

and it seemed to me that we had never imagined it properly."

From then on collections of stories and novels

followed. One of them, the historical novel Oscar and Lucinda, rewarded

him with the Booker Prize in 1988. But among his works, the book that

probably celebrates Australia best is True History of the Kelly Gang.

"I was born in Australia and lived there until a few years ago," he starts

recounting, "Australia still seems to remain the main subject and obsession

of my novels. I lived in New York City for the past eleven years. I did

once tried to wrote a novel abut the United States, but it was with great

relief that I abandoned it. The reason I abandoned it was that it somehow

occurred to me that there was this great Australian story about an outlaw

called Ned Kelly that had never been told. And what was very interesting to

me from the perspective of the United States was not that he was just an

outlaw like Jesse James, but that this outlaw's story was the single most

important story in our culture. It wasn't like he was Jesse James. It was

more as if he was Thomas Jefferson and Abraham Lincoln and George

Washington rolled into one. In the perspective of New York this looked very

strange, you know, living away from home one has this benefit of seeing

what was familiar as strange to understand. For example, the lyrics of the

song 'Waltzing Matilda', a famous song in Australia that politicians never

seem to be able to accept as our national song, are about a homeless man

who steals a sheep and commits suicide rather than go to jail. This is a

song about heart, in Australia this seems normal, but from the distance of

New York one can see how wonderful and peculiar this is. We love Ned Kelly

in the same way that we sympathise and in a way identify with the homeless

man who committed suicide. I thought Ned Kelly's story was a great story

and it seemed to me that we had never imagined it properly."

True History of the Kelly Gang contains thirteen diaries written by Edward "Ned" Kelly himself for his daughter's benefit: in the diaries the outlaw recounts his own story, from his childhood through his apprenticeship with bushranger Hart, to his experiences and adventures as thief, bank robber, jailbird or farmer. "Most of the Europeans who came to Australia were actually convicts, they were in a way marked by an evil convict stain," Carey reminds us regarding the Irish origins of Ned, "at that time, people wondered if they could have ever formed a civil society and so did the convicts themselves."

Many were the biographers who tried to

track down the truth regarding Ned Kelly's life. Among the others were Keith

McMenomy in his book Ned Kelly: The Authentic Illustrated History and Ian

Jones in Ned Kelly: A Short Life. Carey claims that it was the latter

that helped him while writing the novel, underlining how, contrary to what

a reader might expect, he didn't spend all his time doing research before

starting to write his novel: "I was not really interested in historical

research about the Kelly Gang, I wasn't interested in primary documents, I

was interested in how we told ourselves the story, I was interested in what

we haven't bothered to imagine. I did a lot of research, but much of it was

about the period and the place. For instance, for this story to work, you

have to realise it was a story of poor farmers, of Irish people, of people

who were madly in love with horses. So, to write about them, you have to be

really able to write about horses to be totally convincing to anybody who

spent a lifetime with them. I'm terrified of horses myself and I had to

face research challenges like that rather than digging in the library

finding primary documents."

Many were the biographers who tried to

track down the truth regarding Ned Kelly's life. Among the others were Keith

McMenomy in his book Ned Kelly: The Authentic Illustrated History and Ian

Jones in Ned Kelly: A Short Life. Carey claims that it was the latter

that helped him while writing the novel, underlining how, contrary to what

a reader might expect, he didn't spend all his time doing research before

starting to write his novel: "I was not really interested in historical

research about the Kelly Gang, I wasn't interested in primary documents, I

was interested in how we told ourselves the story, I was interested in what

we haven't bothered to imagine. I did a lot of research, but much of it was

about the period and the place. For instance, for this story to work, you

have to realise it was a story of poor farmers, of Irish people, of people

who were madly in love with horses. So, to write about them, you have to be

really able to write about horses to be totally convincing to anybody who

spent a lifetime with them. I'm terrified of horses myself and I had to

face research challenges like that rather than digging in the library

finding primary documents."

Carey's book is written in a peculiar style that tries to capture Kelly's language: "The historical figure of Ned Kelly left behind a fifty-six page letter written in very bad grammar, but with a great deal of passion and beauty and it seemed to me this was the character's DNA and, if I could inhabit this world in some way, I could make this man stand up and walk around again and make poetry from an uneducated poet. To me, this was quiet a moving idea, because that voice was never heard in his lifetime and it was quite ambitious to even think of giving voice to the voiceless. There were two or three risky things about taking on this book: one is to abandon the comma as Ned Kelly did. Ned Kelly was a busy man and didn't have time for commas and sometimes he forgot full stops as well. I wanted to write in this way, but still I didn't want to leave my readers confused."

"The other rather dangerous thing to avoid doing was to take on a national story and mess with it. But people were generally happy with the result. I often had writer's block while writing the novel. It always happens to me when I write. For me there will be at least ten or twenty times, while writing a novel, when I get to a point and get stuck, but it's part of the process and normally my first draft gets to 80 pages before I'll think 'I don't know what I'm doing.' So I go back to the beginning, figure out what I haven't understood, what I'm not telling the truth about, what I haven't investigated enough with characters I haven't imagined, then I'll go on again and it will happen again."

"There were parts in this book that caused me quite a few problems. For example, the primary relationship that Ned Kelly seems to have with his mother: to me it was an exciting insight looking at the historical records, but, to make the story work, I had also invented a child, then I had invented the mother of the child, and, consequently, I had invented the relationship between Ned and this woman. There are certain times as the story progresses when you have the relationship with the mother and the relationship with the woman in the gang, but you can't really have both, since both of them are of equal importance. For a while I tried to have both of them in the story, but the plot really spun out of control, so I had to get rid of the mother of the child and let this story be about the son and the mother."

After two literary prizes chances are that this novel on Ned Kelly will also be transposed on the big screen. "Neil Jordan did option this book," Carey announces, "we had dinner in Dublin and he said 'It's a very nice novel, would you like to write the screenplay?' and I said 'No!' because why would I want to do it when one of the most exciting things about writing the screenplay for this movie would be when such a director and writer takes his own obsessions and his own Irish take on this story? What's exciting to me is what he would write. I think that a novel is not a film and a film is not a novel and the person making the film has to destroy the novel in order to remake it. It would be easier for Jordan to write the screenplay for my novel."

Talking about writing techniques, leads us to a discussion on the theory of writing. Apart from being a novelist, Carey actually taught creative writing for quite a few years at the University of New York. "I think there's a lot of misunderstanding about 'teaching' creative writing. I think you can't never give anybody talent, if people don't have stuff they're obsessed with writing about, then you can't give them that and you certainly can't give them wisdom. But there are technical things you can work with writers almost like an editor does and there are quite a few very simple craft tricks which a good writer will find out for himself or herself in the end. You can maybe save them a little time teaching them these tricks and, at the same time, in this way, you cannot damage them too which is an important responsibility."

Though living and teaching in New York, Carey doesn't seem to be too isolated from his home country not to follow the new stars of Australian literature. "I think what I've learnt in the last few years is that there has been once again a flowering of Australian writing," he admits, "writers such as Richard Flannigan are really exciting authors, but there are also other writers with new, strong, original voices. You see, for a long long time I felt like the writers of my generation had lost their voices, it looked as some of us were getting tired and I wondered if the new voices had been sucked in the film or television business, but it's not true, good exciting strong voices are emerging again. Australian writers have a style of their own, I'd be very surprised if we didn't have our own voice and style, but when you're one of them, when you're in the middle of the muddy business of making literature, I think it's very hard to step back and say how you're the same or different from your fellow country men and women. I'm a great believer in national differences, so I'm sure we have differences from writers who come from other countries, but I can't see how."

To find differences or analogies with other writers coming from different countries, Carey might turn to Ian McEwan, to whom he said during the Booker Prize awarding ceremony that he was "indebted": "Ian is a friend of mine. At the time of the Booker Prize we had a bet," he laughs, shaking his head. "He and I were both opted for the 2001 Booker Prize and we had a wager: the winner would have had to bring the other to a very expensive meal. So, when I accepted the prize, I had to give thanks to people I was indebted to. I was indebted to my son who was there, to my wife and to…Ian McEwan for a meal! That dinner cost me $500, it was a good bet..."

Gossips, jokes and bets about the Booker Prize aside, Carey seems to be already engrossed in finishing his new novel. "By Christmas it will be three years since I've finished Ned Kelly, so I'm hoping that the book I'm doing right now will be finished by then, it's a book called My Life as a Fake and it's based on something that happened in Australia in 1946 when some conservative poet invented an avant-garde poet as a hook to humiliate someone. And in my novel the poet really comes to life and, like Frankenstein's monster did, torments his creator. It's set in Australia a little bit more recently than Ned Kelly." Perhaps time has come for Carey to move on and create another character and a new story to tell, but the Ned Kelly he brought back to life in True History of the Kelly Gang will sort of remain stuck in his readers' minds.

"I were the terror of the government being brung to life in the cauldron of the night", Ned Kelly proclaims at the end of his eleventh diary, remembering the readers an angry and rebellious Lucifer rather than an illiterate scoundrel. The Australian hero has finally found his voice, a voice that, filtered through Peter Carey's style, is bold, powerful and strong, like the famous iron armour Ned Kelly wore in his last shoot-out.

Copyright (c) 2005 erasing clouds |

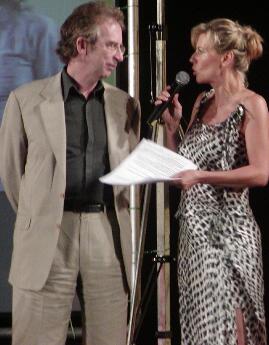

Peter Carey's pic by Anna Battista. |