Total Assault on (Fascist) Culture: an afternoon with Fernanda Pivano and Dan Fante

by Anna Battista

"So, why aren't you married right now? What happened? You don't think it's worthy anymore?" she asks.

"I like the ceremony, it's what comes afterwards that I don't like…" he promptly replies, bursting into laughter.

It all starts with a few jokes, as if they had been friends for a long time

and were only rejoicing now after too many years. But, actually, this is

the first time they meet. She's the Italian writer Fernanda Pivano, Nanda

for her closest friends and admirers; he's the American writer Dan Fante.

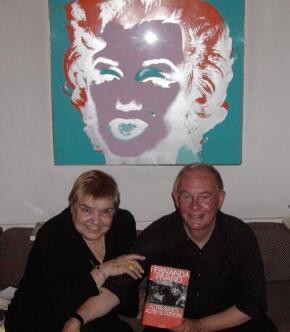

They're both sitting on a sofa in Nanda's house, in Milan, under an Andy

Warhol Marilyn Monroe painting donated by Andy himself to Nanda many

years ago, a work of pop art that still preserves the magic and madness of

its author and of those times. Dan is in Italy for a small tour, while

waiting for his novel Spitting Off Tall Buildings (Canongate) and his

anthology of poems A Gin Pissing Raw Meat Dual Carburettor V8 Son of a

Bitch from Los Angeles (Sun Dog Press) to come out in America. Dan and

Nanda have something in common, their American publisher: Dan's publisher

Sun Dog Press released a couple of years ago Charles Bukowski: Laughing

with the Gods, a beautiful and touching interview Nanda did with an author

she truly cherished and loved. And a good visit to Fernanda is a way of

relaxing, but also of getting to know better a woman who has spent most of

her life trying to get American authors published in Italy.

It all starts with a few jokes, as if they had been friends for a long time

and were only rejoicing now after too many years. But, actually, this is

the first time they meet. She's the Italian writer Fernanda Pivano, Nanda

for her closest friends and admirers; he's the American writer Dan Fante.

They're both sitting on a sofa in Nanda's house, in Milan, under an Andy

Warhol Marilyn Monroe painting donated by Andy himself to Nanda many

years ago, a work of pop art that still preserves the magic and madness of

its author and of those times. Dan is in Italy for a small tour, while

waiting for his novel Spitting Off Tall Buildings (Canongate) and his

anthology of poems A Gin Pissing Raw Meat Dual Carburettor V8 Son of a

Bitch from Los Angeles (Sun Dog Press) to come out in America. Dan and

Nanda have something in common, their American publisher: Dan's publisher

Sun Dog Press released a couple of years ago Charles Bukowski: Laughing

with the Gods, a beautiful and touching interview Nanda did with an author

she truly cherished and loved. And a good visit to Fernanda is a way of

relaxing, but also of getting to know better a woman who has spent most of

her life trying to get American authors published in Italy.

Born in 1917 in Genoa, Nanda was destined to understand really soon the limitations and restrictions imposed by fascism. "When I was a young girl, I lived in a fascist country where you couldn't publish anything," Nanda explains, "My grandfather was British, actually he was Scottish, and was the founder of the Berlitz School. He came to Italy to introduce the school in the country. I used to live in a way that wasn't really provincial, I was also taught in a Swiss school and this way of living was against the fascist provincial rules of life. Then I heard the first ideas of democracy coming from the States: at the time there was Roosvelt in America and Roosvelt was very fascinating for us. Somehow, through the underground Italian anti-fascist movement, I had read the speech he had done on the fourth liberty, the freedom from fear. This liberty was very important for us because we had the fear of being arrested all the time. This man was talking about freedom, so for us, for the antifascists of that time, the American dream was Roosvelt." "I agree with Nanda," Dan adds, "During World War II, Roosevelt communicated that anything was possible for the average man. The world believed him. Today the American Dream is spoon fed to Americans on TV. Bigger! Faster! More! Win at any cost!"

Nanda started her career as translator in 1943, with a translation of Edgar Lee Masters' Spoon River Anthology, but it was in 1956, when she first went to the States, that a new world opened up for her. She got in touch with the Beat writers and from then on, her life changed: she started translating new and revolutionary authors, then brought them to meet Italian editors and wrote beautiful introductions for their books. When Nanda speaks it's like seeing many of her American icons coming back to life: Marilyn, as Nanda remembers with loving affection, was a little darling, Kerouac a handsome man, Bukowski a man with a temper whom she fondly admired, with a wife, Linda, who had fallen in love with Nanda's green shoes.

"What struck me the first time I went to the States was the space. America was so big, so large to my eyes. We were coming from a small country and I suddenly found six lines of cars coming from the airport!" Nanda recollects, "I was really really amazed! I found at the airport waiting for me Hannah and Matthew Josephson. Hannah was the librarian of the American Academy and Matthew was a big author, he had written the Zola biography and he had also published in 1934 The Robber Barons, a beautiful book, a marvelous book, one of the first denunciation books on Wall Street. They showed me The New Yorker on which there was an article about Edmund Wilson talking about an introduction I had written in Italy. So Matthew said 'This is a welcome for you!' you see, right at that time Edmund Wilson was very famous. But that wasn't very important for me. Indeed, one of the most important things that happened to me when I visited the States was when they took me to meet Norman Mailer. Mailer was very bold, handsome with his beautiful blue eyes. He was also a little insolent, but I really liked him and Adele was a very beautiful woman. I remember Adele telling me 'If you want to get an elegant dress in the States, you don't have to eat, otherwise you won't find anything and will have to buy the dresses that they make for the negro women who are big. If you're small you don't have to, but to be small, you don't have to eat!' She taught me the real American rule of beauty! Adele was very sweet!"

During her life, Nanda also worked as research assistant for the Faculty of Philosophy at the University of Turin, but this experience was probably one of the most negative of her life. "I think the academic world is horrible," she starts, "it is conservative, it prohibits, it forbids any kind of new way of thinking, it is against reality. Young people have to be and are projected into the future we, old people are projected into the past, we try to remember and be nostalgic, young people simply don't know what you're talking about when you talk about the past. And the academics are the machinery that stops culture, they only speak of the past, they don't know anything of the present."

"And they have no voice," Dan intrudes, "their

voice is an echo, it is not creative!" "When they ask me what's the

difference between the work I've done and the academy," Nanda nods to what

Dan has said and continues, "then I say that the thing I've done is to work

like an ethnographer, I work on the field, going and trying to meet the

authors and trying to find out who the authors are and what they want.

Authors, writers are so different in reality from the stereotypes created

by the media. I wanted to know who they really were, that was what I was

trying to do, that's why I wanted to see them…naked!" Nanda concludes

laughing, "But, you're going to see ME naked!" Dan suggests, with a broad

smile on his face, "Please don't!" Nanda exclaims, before continuing, "The

professors never try to speak with an author, they don't read the author,

they read what the other professors have written about that author…" "The

author is the conscience of any society," Dan claims, "he tells the truth -

his truth. He is the reflection of his times. While academics only read

what their peers said about that author, and…they are completely anal,

these people have no rectum, no arsehole! Nothing ever comes out of their

back end because they're…" "Sir, behave!" Nanda laughs, but Dan is ready to

remark, "It's true! It's an establishment that is self-perpetuating, that

doesn't allow new talent…this is what the academy is in the States, this is

the publishing business there."

"And they have no voice," Dan intrudes, "their

voice is an echo, it is not creative!" "When they ask me what's the

difference between the work I've done and the academy," Nanda nods to what

Dan has said and continues, "then I say that the thing I've done is to work

like an ethnographer, I work on the field, going and trying to meet the

authors and trying to find out who the authors are and what they want.

Authors, writers are so different in reality from the stereotypes created

by the media. I wanted to know who they really were, that was what I was

trying to do, that's why I wanted to see them…naked!" Nanda concludes

laughing, "But, you're going to see ME naked!" Dan suggests, with a broad

smile on his face, "Please don't!" Nanda exclaims, before continuing, "The

professors never try to speak with an author, they don't read the author,

they read what the other professors have written about that author…" "The

author is the conscience of any society," Dan claims, "he tells the truth -

his truth. He is the reflection of his times. While academics only read

what their peers said about that author, and…they are completely anal,

these people have no rectum, no arsehole! Nothing ever comes out of their

back end because they're…" "Sir, behave!" Nanda laughs, but Dan is ready to

remark, "It's true! It's an establishment that is self-perpetuating, that

doesn't allow new talent…this is what the academy is in the States, this is

the publishing business there."

Apparently, the publishing business and the academy aren't very different in Italy. "You see, at the beginning it was the fascist movement that was holding Italians back from knowing these American writers, then it was the academy," Nanda explains, "You don't know what the academy did to me, professors taught me treating me like a stupid. It was terrible, I was insulted all the time, but these new books were beautiful books and these new writers were beautiful writers, damn it! They had to be published! It was just the presumption, the stupidity, the ignorance of this bunch of people that was avoiding other people to know them. That was the story. When I met the Beats they were nobodies, they were young, they were perhaps 18 years old boys. Once they revealed to me 'We were really surprised by the fact that such an elegant woman like you had come to meet us, you seemed to be the only one who knew what we had written when nobody had ever heard about us'. At that time Allen Ginsberg hadn't even published 'Howl'. The first time I heard of 'Howl' was when I was in Puerto Rico with William Carlos Williams, we were at a party and he said that he was going to do the introduction for a young poet from Patterson, since he was also from Patterson. He told me he thought that this poet was intelligent and brilliant. Then, in 1957, I went to Paris and I saw the second issue of the 'Evergreen Review' and I found 'Howl' inside it. That was the beginning of the resistance for me: I wrote a letter and in 1960 Gregory Corso came to meet me."

"Gregory was the ambassador of the Beats. He was completely nuts, my God! He arrived in Milan from Paris, so I asked him 'Do you want to take a shower?' and he roughly said 'What do you mean, do I smell?' And from then on, while Gregory was staying at my house, all my rules were completely broken, I really had to change my rules of life. I decided that offering him coffee wasn't the right thing to do, so I said 'Do you want a joint?' but I didn't have it and he said 'Yes, I think that would be a great idea!' I had to change my way of thinking and living, the Beats really changed my life. After Gregory paid me a visit, he met Kerouac and told him 'She's pretty, she's not a prude!' so Kerouac started calling me at four o'clock in the morning, you see, you couldn't even think of explaining the time zone to him, and he asked me 'At what time does the plane to Milan leave? I want to come and meet you!' From then on we started talking and building a sort of antifascist movement…" "You might say you were literary antifascists!" Dan enthuses, "Yes, we were," she admits, "I think that 'Howl' was a big thing and 'Bomb' was a big thing and 'On The Road' was a big thing. So this is my Beat Story."

"I think that in those days things that had never been published before were being published," Dan points out, "so you had to take the good with the bad. For instance, when you read Burroughs, some of it is a kind of madness, of pure rambling madness..." "But Burroughs was the beginning of the postmodernist movement," Nanda remarks, "I still keep on liking Hubert Selby Jr. best," Dan reveals, "he is my favourite writer of those days, he was not widely regarded as a Beat Writer but he did write at the same time and was certainly better than any of the so-called Beats." "Well, I miss all the Beats!" Nanda replies, "but I miss most of all Ginsberg, Kerouac and Corso, because they were three monsters. You know, I used to work with Ginsberg for hours on end. He came on purpose to work with me, to assist me in the translation of his poems and we enjoyed working together. The best thing of working with such writers was that I could understand them and see how different they were from the image the media had created of them."

After two seconds of silence Nanda asks us if we want to hear what she calls "The Story of Hemingway." We nod and she sets to tell us a wonderful tale: "The story of Hemingway is another thing. The publisher Einaudi gave me a contract to translate A Farewell to Arms. At that time the book was forbidden by Mussolini, but Einaudi had already started preparing the book, because we all knew that Mussolini would have fallen, you see, it was very easy to understand it! Einaudi and I were very much involved in the whole thing, but then the Nazis arrived and, while I remained in Turin, Einaudi ran away to Rome. The Nazis arrested me after an enquiry they made at the publishing house where they had found my contract with Hemingway. As I said Hemingway was forbidden, so they had a reason to arrest me. They wanted to know where Einaudi was and I didn't tell them, I really didn't tell them!"

"The first interrogation started in the morning at 7 o'clock, then there was another one at midnight. I was playing saying 'How could I have ever done something like that, I'm so young! A girl like me? It's impossible!' This went on all day, then the terrible moment came in the morning when they wanted me to say that I wasn't the translator, but the publisher, they wanted me to write down that I was the "Herausgeber" and not the "Übersetzer". I knew the difference between the two words and I refused to comply. When they found out that I knew the difference between the two words they said 'We see you know some German, so you don't need an interpreter anymore' but I didn't know enough German and I was really frightened because they could have sent me to a concentration camp. It looked like it was the end. But then they said 'Now you go, but, from now on, you will have a German officer or a soldier who will check what you're doing' and they gave a beautiful boy who had to follow me around."

"After the war I started doing other things. In 1948 Hemingway arrived in Italy and sent me a postcard saying 'I want to meet you, come to Cortina' and I thought it was an joke, I didn't believe it. But after a week he sent me another postcard in which he added 'If you don't come to Cortina, I will come to Turin!' I suddenly found myself on the train to Cortina. It took me nine hours to reach the place, you also had to take a train that ran through the mountains, it was really like a sci-fi story, but I managed to arrive at the hotel. I was dirty because there were no windows in the train, it was 1948 and the train was coal-fueled. So I was all black and when I arrived at the hotel I got into the dining room where Hemingway was having dinner. He liked to have a lot of people at table, he used to say that he wasn't making presents, he was 'giving out food', for him food was a present, he had this archaic but very poetic way of talking…yes, I know that whatever I say about Hemingway is partial! Anyway, he immediately understood that it was me, he crossed the big room with open arms and I nearly fainted, he gave me a big hug and said, with his slightly stammering voice, 'Tell me about the Nazis'. So, I understood that he knew everything, he always knew everything, I don't know how he could do it, but he did and I told him all the story about the Nazis. That night he made me sit close to him at the table throwing away the menu that was there and we spend the night talking. At that time Mary had rented a Villa named Villa Aprile, Aprile was the name of the owner not of the month, it was June I think, and I stayed there for a while in his house. This is when he made me translate his works in the morning close to him, from 5 a.m. o'clock till 11 a.m., he was sober, he wasn't drunk and it was a big difference when he was sober. He was often telling me why he was throwing away a part of what he was writing, while he was cutting this or that. Working with him was difficult, but it was like living in a dream, it was really fascinating. Like working with Ginsberg, but Ginsberg wasn't a genius like Hemingway." Between 1947 and 1965 Nanda translated Hemingway's Death in the Afternoon, A Farewell to Arms and Across the River and Into the Trees, but she also worked on The Old Man and the Sea. "That's my favourite book by Hemingway," Dan tells Nanda, "Hemingway had a great influence on me as a stylist. He had great simplicity and power. I also much admire his work ethic and do as he did: write in the morning before getting drunk or...whatever."

From the '40s on, Nanda translated a lot of authors, including William Faulkner, Francis Scott Fitzgerald, Gertrude Stein and Richard Wright, to mention a few of them, so she is the right person a translator might turn to for some good advice. "When you translate a text, you have to completely forget yourself," Nanda underlines, "you must try to mould yourself into the page that must be translated." "To be a good translator," Dan intervenes, "a person must thoroughly understand the author's intent, know all his work, but most importantly, his nuances, his sub-text, what he really means by what he was saying." Dan is at present working on a collection of short stories, Short Dog, but he's also thinking about writing a biography of his dad, the writer John Fante. Meanwhile Nanda, whose books of essays and articles about American writers Beat, Hippie, Yippie (Bompiani), Amici Scrittori (Mondadori), Altri Amici (Mondadori) and Viaggio Americano (Bompiani), to mention the main ones, are confirmed as the pillars of any bibliography about American literature, seems to have other plans, "When someone asks me 'What would you like to do in a next future?' I always answer 'I want to be a whore, but nobody lets me to be a whore!' I also say this in a movie about me! usually when it's on the screen there's a big round of applause and people madly clap," she laughs, then she changes her tone of voice and becomes serious once again, "but, then, if you ask me what I REALLY would like to do, I'll tell you that I would like to write three lines that people will remember forever. I still haven't done it, perhaps I will never write them, but this is what I'd like to do."

"All I ever wanted was to think clearly enough to put down one sentence," Dan admits.

"It was the same for me…" Nanda adds.

"And because I was so mad and so unstable I couldn't do it. When I began, I completed the draft of my first book after three months and I realised it was awful. So I started working on it and, you know what? I discovered that there WAS a good sentence in it and I knew that there was a chance for me…"

"So you've been lucky, you wrote a good sentence! But I still haven't! Young people write a lot of stuff to me, they love me so much, and they often tell me: it's as if you had already written those three lines and they will always be in our hearts forever. And when I read such stuff I always start crying, I'm so stupid!

"I always answer my readers and young people who write me, they sometimes write about my father and they write with such love that you must answer. They often ask me 'How do I write? What should I do? Where do I begin?'"

"It's a terrible responsibility!"

"You know what I tell them? Sit down everyday and write just one hour, then do it six days a week for one year, because, you see, I never could write a book, but I could write one page a day. And one page a day in two hundred days is two hundred pages. I've never been able to write a book, but I can write a page a day, because I can't think of the scope of a novel I must think about the moment and what I'm doing now. That's also how I write poetry, I write one poem a day."

"This is a very good idea, I will copy it! I'll quote you!"

"If I can write one good page a day, I will be king of the world, because that's what a writer is, he's a builder, he's a stone mason, he puts one stone on top of another stone and if he sees that the level isn't right he takes a stone away and puts in another stone."

"Bravo! That's very good! I'll quote you!"

"I'll quote YOU!"

"I have nothing that can be quoted…" Nanda humbly says.

"Oh, STOP it!" Dan rebukes her.

"I have only to quote that I didn't say to the Germans the address of where Einaudi was! They didn't believe me, they knew that I was lying," Nanda concludes, a beatific smile on her face. And that radiant smile doesn't even turn into a nasty sarcastic grimace when she's asked something about the centre-right wing government ruling Italy right now. "I speak of sex", she declares, avoiding talking on such a matter. "I speak of peace and love," she adds, showing Dan the Yin Yang locket that adorns her neck. Perhaps she's already written the famous three lines, perhaps she hasn't. But what Fernanda Pivano has surely done is give her life to literature, giving Italy the chance to be introduced to great authors such as the Beats and lately Dan Fante. "His books truly are love and death ballads, like Charles Bukowski's and like John Fante's," Fernanda wrote in a recent article in the Italian newspaper Il Corriere della Sera, about Dan's works. "His novels can destroy everything: marriages, jobs, and family. He shows us a slow descent into hell. He is persecuted by the demons of alcohol and madness but at the same time we see a deep search for salvation … Surely he has written beautiful words, sincere as heart-rending." And if these words come from such a literary authority as Nanda we can genuinely believe them.

Copyright (c) 2005 erasing clouds |

Pics by Anna Battista. |